Credit risk is one of those concepts that can take a minute to learn and a lifetime to master. Every year a noticeable share of the world’s financial assets are charged each year by credit analysts and rating agencies to answer the simple question “how likely is it that this borrower will pay me back?”

Spreadsheet wizards naturally start looking at credit by modelling cash future cash flows, and calculating the probability that those cash flows will fail to be enough to service the given class of debt. For corporate borrowers, analysts can use simple measures like Altman’s Z-score, but as seen with Bitcoin and other capital controls, sovereign risk not only has to deal with the ability of the cash flows to pay the debt, but the willingness of the sovereign and its supporting legal system to pay, with recent examples being Greece and Detroit. Here, the big difference between companies and countries is that countries usually don’t “go away” the same way countries do – even when a country’s government dissolves or is conquered, the land and people generally stay put, and there are political and financial reasons to refrain from confiscating property and repudiating the previous regime’s debt.

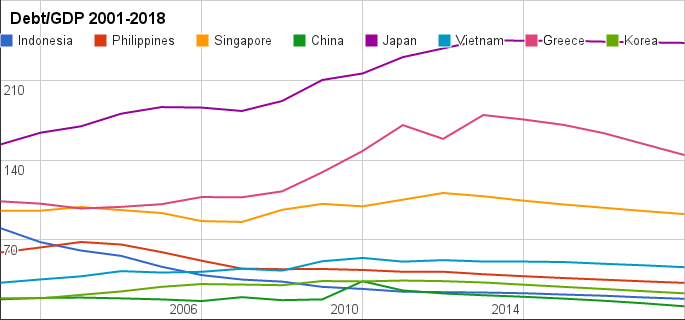

Rather than start a history book on government debt at this point, I would rather look at some simple statistics that tell a story about sovereign risk in Asia over the past decade and perhaps the decade to come. Debt/GDP ratios are derived from the IMF’s WEO database and credit ratings in this case are simply pulled off the S&P website.

This table shows select how select countries’ debt/GDP ratios have increased or decreased from 2002 to 2012 vs their current S&P foreign currency credit ratings. While this is too small a sample to generalize, it generally seems that (with the exception of Greece, Kuwait and Vietnam) countries that are still ranked as riskier (B- to BBB+) have generally been outgrowing their debt over the past decade while the still-named “high grade” countries (A- to AAA) have been the ones whose debts are outgrowing them.

| Country | Change in Debt/GDP 2002-2012 | S&P FC Rating |

| Kuwait | -77.39% | AA |

| Indonesia | -64.60% | BB+ |

| Turkey | -50.83% | BB+ |

| Philippines | -33.73% | BBB- |

| Kazakhstan | -29.98% | BBB+ |

| Cambodia | -28.38% | B |

| Pakistan | -21.71% | B- |

| Thailand | -19.62% | BBB+ |

| India | -18.68% | BBB- |

| Lebanon | -13.31% | B |

| Bahrain | 5.19% | BBB |

| Singapore | 16.23% | AAA |

| Italy | 20.52% | BBB |

| China | 20.66% | AA- |

| Hong Kong SAR | 21.67% | AAA |

| Malaysia | 28.84% | A- |

| Taiwan Province of China | 34.64% | AA- |

| Japan | 45.08% | AA- |

| Vietnam | 48.07% | BB- |

| France | 52.94% | AA+ |

| Greece | 55.96% | B- |

| Korea | 81.40% | A+ |

Some of the effects of this trend have been seen with the upgrade of Indonesia and Philippines to investment grade vs the downgrades of the US and France, but a greater example of how analysts and agencies can’t be too far ahead of the curve is when the credit default swap for France was trading wider than these islands’:

For someone who likes to travel as much as I do, the feel “on the ground” definitely seems to correlate more with a country’s credit rating than a simple quantitative measure like debt/GDP. It is largely relative feelings of order and “ease of getting around and getting things done” which is why despite charts like the ones below, so many investors might intuitively consider Japan and Singapore far less risky than Vietnam.